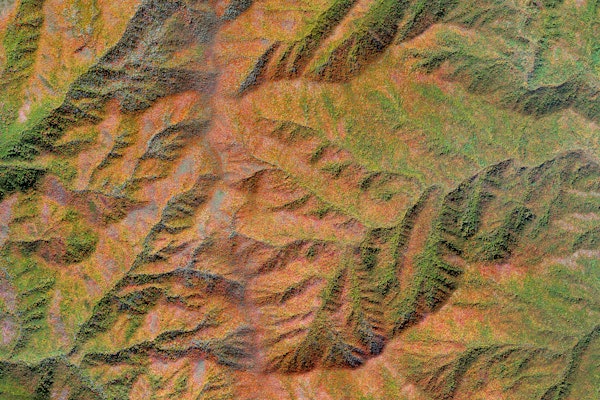

Border Lines

An Overview perspective of the U.S / Mexico Border

A series of border barriers draws a stark line between Yuma, Arizona (top) and San Luis Río Colorado in Sonora, Mexico (bottom). San Luis Río Colorado has exploded into a city of nearly 200,000 people thanks to its booming maquila factories. These factories manufacture large quantities of goods at cut rate prices for established American companies. In contrast, Yuma is home to just 96,000 residents. (Source imagery: Maxar)